Everyday Life and Cultural Theory an Introduction Review

Cultural-historical activity theory (CHAT)[1] is a theoretical framework[2] which helps to understand and analyse the relationship betwixt the human listen (what people recall and feel) and activeness (what people practise).[3] [4] [5] Information technology traces its origins to the founders[6] of the cultural-historical school of Russian psychology Fifty. Due south. Vygotsky[7] and Aleksei Due north. Leontiev.[8] [9] [ten] [11] Vygotsky's important insight into the dynamics of consciousness was that information technology is essentially subjective and shaped by the history of each individual'due south social and cultural experience.[12] Especially since the 1990s, Chat has attracted a growing interest amongst academics worldwide.[13] Elsewhere CHAT has been defined equally "a cross-disciplinary framework for studying how humans purposefully transform natural and social reality, including themselves, as an ongoing culturally and historically situated, materially and socially mediated process".[14] Cadre ideas are: 1) humans act collectively, larn by doing, and communicate in and via their deportment; two) humans make, utilise, and adapt tools of all kinds to learn and communicate; and three) community is primal to the process of making and interpreting meaning – and thus to all forms of learning, communicating, and acting.[fifteen] [16]

The term Conversation was coined by Michael Cole[17] and popularized by Yrjö Engeström[eighteen] to promote the unity of what, by the 1990s, had go a variety of currents[19] harking back to Vygotsky's piece of work.[20] [21]

Historical overview [edit]

Origins: revolutionary Russian federation [edit]

Conversation traces its lineage to dialectical materialism, classical German philosophy,[nine] [22] [23] and the work of Lev Vygotsky, Aleksei N. Leontiev and Aleksandr Luria, known as "the founding troika" [24] of the cultural-historical arroyo to Social Psychology. In a radical deviation from the behaviorism and reflexology that dominated much of psychology in the early 1920s, they formulated, in the spirit of Karl Marx's Theses on Feuerbach, the concept of activity, i.eastward., "antiquity-mediated and object-oriented action".[25] [26] Past bringing together the notion of history and culture in the agreement of human activity, they were able to transcend the Cartesian dualism between subject field and object, internal and external, betwixt people and guild, between private inner consciousness and the outer world of society.[27] Lev Vygotsky, who created the foundation of cultural-historical psychology, based on the concept of mediation, published vi books on psychology topics during a working life which spanned only x years. He died of TB in 1934 at the age of 37. A.N. Leont'ev worked with Lev Vygotsky and Alexandr Luria from 1924 to 1930, collaborating on the development of a Marxist psychology. Leontiev left Vygotsky's group in Moscow in 1931, to take up a position in Kharkov. There he was joined past local psychologists, including Pyotr Galperin and Pyotr Zinchenko.[28] He connected to work with Vygotsky for some time but, eventually, there was a split up, although they continued to communicate with one some other on scientific matters.[29] Leontiev returned to Moscow in 1934. Reverse to popular belief, Vygotsky'due south piece of work per se was never banned in Stalinist[30] Soviet Russia.[31] In 1950 A.N.Leontiev became the Head of the Psychology Department at the Faculty of Philosophy of the Lomonosov Moscow Land University (MGU). This department became an independent Faculty in 1966 due mainly to his hard work. He remained at that place until his death in 1979. Leontiev's conception of action theory, post 1962, had become the new "official" basis for Soviet psychology.[32] In the ii decades between a thaw in the suppression of scientific enquiry in Russia and the death of the Vygotsky's continuers,[33] contact was made with the West.

Developments in the Westward [edit]

Michael Cole, and so a young Indiana University psychology mail-graduate commutation student, arrived in Moscow in 1962 for a ane-twelvemonth stint of research under Alexandr Luria. Keenly aware of the gulf between Soviet and American psychology, he was one for the first Westerners to present Luria's and Vygotsky's idea to an Anglo-Saxon public.[34] [35] This, and a steady menses of books translated from the Russian[36] ensured the gradual institution of a solid Cultural Psychology base of operations in the w.[37] Another American scholar, James Five. Wertsch, subsequently completing his PhD at the Academy of Chicago in 1975, spent a twelvemonth as a postdoctoral swain in Moscow to study linguistics and neuropsychology. Wertsch subsequently became 1 of the leading Western experts on Soviet Psychology.[38] Principal among the groups promoting Conversation-related research is Yjrö Engeström's Helsinki-based CRADLE.[39] In 1982 an Activeness Briefing, claimed to have been the first of its kind in Europe, organized by Yrjö Engeström to concentrate on teaching and learning problems, took place in Espoo (Fl), with the participation of experts from both Eastern and Western European countries. This was followed by the Aarhus (Dk) Conference in 1983 and the Utrecht (Nl) conference in 1984. In October 1986, W Berlin's College of Arts hosted the first ISCAR[forty] International Congress on Action Theory. This was as well the first attempt to bring together under one roof researchers, theorists, and philosophers working in the tradition of the Soviet psychologists Leontiev and Vygotsky.[41] The second ISCRAT congress took identify in Lahti, (Fl) in 1990. ISCRAT became a formal legal organization with its own by-laws in Amsterdam, 1992. Other ISCRAT conferences: Rome (1993), Moscow (1995), Aarhus (1998) and Amsterdam (2002), when ISCRAT and the Conference for Socio-Cultural Inquiry merged into ISCAR. From here on, ISCAR organizes an international Congress every three years: Sevilla (Es) 2005; San Diego (The states) 2008; Rome (It) 2011; Sydney (Au) 2014; Quebec, Canada (2017).

In more contempo years the implications of activity theory in organizational development take been promoted by the work Yrjö Engeström'southward team at the Centre for Activeness Theory and Developmental Work Enquiry (CATDWR)[42] at the Academy of Helsinki, and Mike Cole at the Laboratory of Comparative Human Cognition (LCHC) at the University of California San Diego campus.[43] [44]

The three generations of activity theory [edit]

In his 1987 "Learning by expanding", Engeström[45] offers a very detailed account of the diverse sources, philosophical and psychological, that inform activity theory. In subsequent years, however, a simplified moving picture has emerged from his and other researchers' piece of work, namely the idea that (to date) there are three principal 'stages' or 'generations'[46] of activeness theory, or "cultural-historical activity theory (CHAT).[47] [48] [49] [l] [51] Whilst the outset generation congenital on Vygotsky'due south notion of mediated action, from the individual'due south perspective, and the second generation congenital on Leont'ev's notion of activity arrangement, with emphasis on the commonage,[52] the 3rd generation, which appeared in the mid-nineties, builds on the idea of multiple interacting action systems focused on a partially shared object, and boundary-crossings between them.[47] [53] [54]

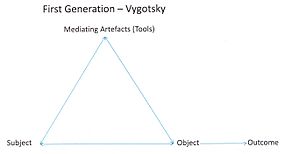

First generation – Vygotsky [edit]

The first generation emerges from Vygotsky's theory of cultural mediation, which was a response to behaviorism's explanation of consciousness, or the evolution of the human mind, past reducing "mind" to a series of atomic components or structures associated primarily with the brain as "stimulus – response" (South-R) processes. Vygotsky argued that the human relationship between a human subject and an object is never directly but must exist sought in society and culture as they evolve historically, rather than in the human encephalon or individual mind unto itself.[55] His cultural-historical psychology attempted to account for the social origins of language and thinking. To Vygotsky, consciousness emerges from homo activeness mediated past artifacts (tools) and signs.[12] [56]

This idea of semiotic mediation[57] is embodied in Vygotsky's famous triangular model[58] which features the Subject (S), Object (O), and Mediating Antiquity triad:[59] in mediated action the Discipline, Object, and Artifact stand in a dialectical human relationship whereby each affects the other and the action equally a whole.[twenty] [21] [60] [61] Vygotsky argues that the utilize of signs leads to a specific structure of human behavior, which breaks away from mere biological development allowing the creation of new forms of culturally-based psychological processes – hence the importance of (cultural-historical) context: individuals could no longer exist understood without their cultural surroundings, nor order without the agency of the individuals who use and produced these artifacts. The objects became cultural entities, and action oriented towards the objects became the key to agreement the human psyche.[62] In the Vygotskyan framework the unit of analysis, nonetheless, remains principally the individual. First-generation activeness theory has been used to understand private beliefs by examining the means in which a person'due south objectivized deportment are culturally mediated.[63] Besides a strong focus on cloth and symbolic mediation, internalization[64] of external (social, societal, and cultural) forms of arbitration, another important aspect of beginning generation Chat is the concept of the zone of proximal development (ZPD),[12] meaning, equally advanced in Mind in Society (1978), "the altitude betwixt the actual developmental level equally determined past independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through trouble solving nether developed guidance or in collaboration with more capable peers".[65] ZPD is one of the major legacies of Vygotsky's piece of work in the social sciences.[66]

Second generation – Leontiev [edit]

While Vygotsky formulated practical human activeness every bit the general explanatory category in human psychology, he did non fully analyze its precise nature. The second generation moves, beyond Vygotsky's individually-focused to A.N. Leontiev'southward[67] collective model. In Engeström'south[45] at present famous graphic depiction of second-generation activity, the unit of analysis has been expanded to include collective motivated activity toward an object, making room for understanding how collective action by social groups mediates action.[68] Hence the inclusion of community, rules, partitioning of labor and the importance of analyzing their interactions with each other.[50] Rules may be explicit or implicit. Division of labor refers to the explicit and implicit organization of the community involved in the action. Engeström[45] articulated the clearest distinction betwixt classic Vygotskian psychology, which emphasizes the way semiotic and cultural systems mediate human action, and Leontiev'due south second-generation Chat, which is focused on the mediational furnishings of the systemic organisation of human activeness.

In insisting that activity only exists in relation to rules, community and sectionalisation of labor, Engeström expands the unit of analysis for studying human behavior from that of private activeness to a collective activity system.[69] [70] The collective activeness arrangement includes the social, psychological, cultural and institutional perspectives in the assay. In this conceptualization context or activity systems are inherently related to what Engeström argues are the deep-seated cloth practices and socioeconomic structures of a given culture. These societal dimensions had not been taken sufficiently into business relationship by Vygotsky'due south, earlier, more 'simple' triadic model:[71] [72] in Leontiev's understanding, thought and cognition should be understood as a function of social life – every bit a part of the means of production and systems of social relations on 1 manus, and the intentions of individuals in certain social weather on the other.[xv] [73]

In his famous example of the 'primeval collective hunt',[74] Leontiev clarifies the crucial difference between an individual activity ("the beater frightening game") and a commonage activeness ("the hunt"). While individuals' actions (frightening game) are unlike from the overall goal of the activity (hunt), they all share in the same motive (obtaining nutrient). Operations, on the other paw, are driven past the conditions and tools at hand, i.e. the objective circumstances under which the hunt is taking place. To understand the split up actions of the individuals, ane needs to understand the broader motive behind the activity as a whole: this accounts for the three hierarchical levels of human functioning:[45] [75] object-related motives drive the collective activity (tiptop); goals drive private/grouping action(s) (middle); conditions and tools drive automated operations (lower level).[76]

Tertiary generation – Engeström et al. [edit]

Subsequently Vygotsky'southward foundational work on the private's higher psychological functions[12] and Leontiev's extension of these insights to collective activity systems,[77] questions of diverseness and dialogue between different traditions or perspectives became increasingly serious challenges, when, especially in the mail-1990s, activity theory 'went international'. The work of Michael Cole and Yrjö Engeström in the 1970s and 1980s – more often than not in parallel, but occasionally in collaboration – brought activity theory to a much wider audience of scholars in Scandinavia and North America.[78] Once the lives and biographies of all the participants and the history of the wider community are taken into account, multiple activity systems need to be considered, positing, according to Engeström, the demand for a "third generation" to "develop conceptual tools to sympathize dialogue, multiple perspectives, and networks of interacting activeness Systems".[79] [80] [81] This larger canvass of active individuals (and researchers) embedded in organizational, political, and discursive practices constitutes a tangible advantage of 2d- and 3rd-generation CHAT over its earlier Vygotskian ancestor, which focused on mediated activeness in relative isolation[82] Third-generation activeness theory is the application of Activity Systems Analysis (ASA)[48] [83] in developmental research where investigators have a participatory and interventionist function in the participants' activities and modify their experiences.

Engeström's[45] at present famous diagram, or basic activity triangle, – (which adds rules/norms, intersubjective community relations, and division of labor, too every bit multiple activity systems sharing an object) – has go the principal third-generation model amidst the research community for analysing individuals and groups.[84] Engeström summarizes the current state of Conversation with five principles:

- The activity arrangement as principal unit of assay: the basic tertiary-generation model includes minimally two interacting activity systems.

- Multi-voicedness: an activity system is always a community of multiple points of views, traditions and interests.

- Historicity: activity systems take shape and go transformed over long stretches of time. Potentials and problems tin only be understood confronting the background of their own histories.

- The cardinal role of contradictions as sources of change and evolution.[85]

- Activity Systems' possibility for expansive transformation (cycles of qualitative transformation): when object and motive are reconceptualized a radically wider horizon opens up.[80] [86]

Nearly often, learning technologists have used tertiary-generation CHAT equally a guiding theoretical framework to empathise how technologies are adopted, adapted, and configured through use in complex social situations.[87] [88] [89]

Informing research and practice [edit]

Leontiev and social evolution [edit]

From the 1960s onwards, starting in the global South, and independently from the mainstream European developmental line,[ninety] Leontiev's cadre Objective Activity concept[91] has been used in a Social Development context. In the Organization Workshop's Big Group Capacitation-method,[92] objective/ized activity acts as the core causal principle which postulates that, in social club to alter the mind-prepare of (large groups of) individuals, nosotros need to start with changes to their action – and/or to the object that "suggests" their activity.[93] In Leontievian vein, the Organisation Workshop is all about semiotically-mediated activities through which (big groups of) participants[94] learn how to manage themselves and the organizations they create to perform tasks that require a complex division of labor.[95]

Chat-inspired enquiry and practice since the 1980s [edit]

Specially over the last two decades, Chat has offered a theoretical lens informing research and do, in that it posits that learning takes place through collective activities that are purposefully conducted around a common object. Starting from the premise that learning is a social and cultural process that draws on historical achievements, its systems thinking-based perspectives permit insights into the real world.[80] [81] [96] [97]

Change Laboratory (CL) [edit]

Alter Laboratory (CL) is a Chat-based method for determinative intervention in activity systems and for research on their developmental potential also as processes of expansive learning, collaborative concept-formation, and transformation of practices, elaborated in the mid-nineties[98] [99] by the Finnish Developmental Work Research (DWR) group.[100] [101] The CL method relies on collaboration between the practitioners of the activity being analyzed and transformed, and academic researchers or interventionists supporting and facilitating collective developmental processes.[80] On the footing of Engeström's theory of expansive learning,[45] [102] the foundation of an interventionist inquiry approach at DWR[101] was elaborated in the 1980s, and developed farther in the 1990s every bit an intervention method now known equally Change Laboratory.[103] [104] CL interventions are used both to study the conditions of change and to assistance those working in organizations to develop their work, drawing on participant observation, interviews, and the recording and videotaping of meetings and work practices. Initially, with the help of an external interventionist, the first stimulus that is across the actors' present capabilities, is produced in the Change Laboratory by collecting first-hand empirical data on problematic aspects of the activity. This data may contain difficult client cases, descriptions of recurrent disturbances and ruptures in the procedure of producing the upshot. Steps in the CL procedure: Footstep 1 Questioning; Step ii Analysis; Stride 3 Modeling; Step iv Examining; Stride v Implementing; Step 6 Reflecting; Footstep 7 Consolidating. These seven activity steps for increased understanding are described by Engeström as expansive learning, or phases of an outwardly expanding spiral,[105] while multiple kinds of actions tin take place at any time.[106] The phases of the model but allow for the identification and analysis of the dominant action type during a particular period of fourth dimension. These learning deportment are provoked past contradictions.[107] [108] CL is used past a squad or work unit or past collaborating partners across the organizational boundaries, initially with the aid of an interventionist-researcher.[97] [103] The CL method has been used in agricultural contexts,[109] educational and media settings,[110] health intendance[111] [112] and learning support.[113] [114]

Activity systems analysis (ASA) [edit]

Action systems analysis is a Conversation-based method,[115] discussed in Engeström 1987/Engeström 1993 and in Cole & Engeström, 1993,[116] for understanding human activeness in real-world situations with data collection, assay, and presentation methods that address the complexities of man action in natural settings aimed to advance both theory and practice. It is based on Vygotsky's concept of mediated action and captures human being activity in a triangle model that includes the subject, tool, object, rule, community, and partition of labor.[45] Subjects are participants in an action, motivated toward a purpose or attainment of the object. The object tin be the goal of an action, the discipline's motives for participating in an activeness, and the material products that subjects proceeds through an activeness. Tools are socially shared cognitive and/or material resource that subjects can use to attain the object. Breezy or formal rules regulate the subject's participation while engaging in an activeness. The community is the group or system to which subjects vest. The division of labor is the shared participation responsibilities in the activity determined by the community. Finally, the outcome is the consequences that the subject faces because of his/her actions driven by the object. These outcomes tin encourage or hinder the subject field's participation in future activities.[117] In Part 2 of her video "Using Action Theory to sympathize human behaviour", van der Riet 2010 shows how activity theory is practical to the trouble of behavior change and HIV and AIDs (in South Africa). The video focuses on sexual practice as the action of the organisation and illustrates how an Activity Arrangement Analysis, through a historical and electric current account of the activity, provides a way of understanding the lack of beliefs change in response to HIV and AIDS. In her eponymous book "Activity Systems Assay Methods.", Yamagata-Lynch 2010, p. 37ss describes 7 ASA case studies which fall "into four distinct work clusters. These clusters include works that help (a) understand developmental piece of work research (DWR), (b) describe real-world learning situations, (c) design human-computer interaction systems, and (d) plan solutions to complicated work-based problems". Other uses of ASA: Summarizing organizational change;[118] Identifying guidelines for designing Constructivist Learning Environments;[119] Identifying contradictions and tensions that shape developments in educational settings;[21] [48] Demonstrating historical developments in organizational learning.,[120] and Evaluating K–12 school and university partnership relations.[121]

Human–computer interaction (HCI) [edit]

When HCI[122] first appeared on the scene as a divide subject in the early on 1980s, HCI adopted the information processing paradigm of figurer science every bit the model for human noesis, predicated on prevalent cognitive psychology criteria, which, information technology was soon realized, failed to account for individuals' interests, needs and frustrations involved, nor of the fact that the technology critically depends on circuitous, meaningful, social, and dynamic contexts in which it takes place.[123] [124] Adopting a Chat theoretical perspective had important implications for understanding how people use interactive technologies: the realization, for example, that a computer is typically an object of activeness rather than a mediating artefact means that people interact with the world through computers, rather than with figurer 'objects'.[4] [125] [126] A number of diverse methodologies outlining techniques for homo–computer interaction design have emerged since the ascent of the field in the 1980s. Most design methodologies stem from a model for how users, designers, and technical systems collaborate. Bonnie Nardi produced the – hitherto – most applicable collection of activity theoretical HCI literature.[four] [127]

Systemic-structural action theory (SSAT) [edit]

SSAT builds on the general theory of action to provide an effective basis for both experimental and analytic methods of studying man performance, using carefully developed units of analysis[128] SSAT approaches cognition both every bit a process and as a structured organisation of deportment or other functional information-processing units, developing a taxonomy of human activeness through the utilize of structurally organized units of analysis. The systemic-structural approach to activity design and assay involves identifying the available means of work, tools and objects; their human relationship with possible strategies of work activeness; existing constraints on activity performance; social norms and rules; possible stages of object transformation; and changes in the construction of action during skills acquisition.This method is demonstrated by applying it to the study of a homo–figurer interaction task.[129]

Hereafter [edit]

Evolving field of study [edit]

The strengths of CHAT are grounded both in its long historical roots and extensive contemporary use: it offers a philosophical and cantankerous-disciplinary perspective for analyzing various man practices as development processes in which both individual and social levels are interlinked, equally well as interactions and boundary-crossings.[54] [130] between activeness systems[131] [132] More recently, the focus of studies of organizational learning has increasingly shifted abroad from learning inside single organizations or organizational units, towards learning in multi‐organizational or inter‐organizational networks, as well as to the exploration and better understanding of interactions in their social context, multiple contexts and cultures, and the dynamics and evolution of particular activities. This shift has generated, amongst others, such concepts every bit "networks of learning"[133] and "networked learning",[134] [135] coworking,[136] and knotworking.[137] [138] Manufacture of late has seen strong growth in nonemployer firms (NEFs), thank you to changes in long-term employment trends and developments in mobile technology[139] which have led to more work from remote locations, more distance collaboration, and more work organized around temporary projects.[140] Developments such as these and new forms of social production or commons-based peer production, such equally east.g. open source[141] development and cultural production in peer-to-peer (P2P) networks, have go a key focus in Engeström's more than recent work.[137] [142] [143]

"4th generation" [edit]

The rapid rise of new forms of activities characterised by web-based social and participatory practices,[144] ,[145] phenomena such as distributed workforce and the authorisation of knowledge work, prompts a rethink of the third-generation model, bringing with information technology the need, equally suggested by Engestrōm, for a new, fourth generation activity system model.[146] [147] which activity theorists indeed take been working on in recent years.[3] [136] [148] In quaternary generation Chat, the object(ive) volition typically incorporate multiple perspectives and contexts and be inherently transient; collaborations betwixt actors, too, are likely to exist temporary, with multiple boundary crossings between interrelated activities.[54] Quaternary-generation activity theorists have specifically developed activity theory to better adjust Castells's (and others') insights into how piece of work organization has shifted in the network society: they hence will focus less on the workings of individual activity systems (often represented by triangles) and more on the interactions across action systems functioning in networks.[140] [149] [150] The 2017 ISCAR congress (August, Quebec City) has the following theme: ''Taking a 360° view of the landscape of cultural-historical activity research:The state of our scholarship in exercise.

See also [edit]

- Activity theory

- Aleksei N. Leontiev

- Bonnie Nardi

- Community of practise

- Cultural-historical psychology

- Expansive learning

- Kharkov School of Psychology

- Knowledge sharing

- Large-group capacitation

- Legitimate peripheral participation

- Lev Vygotsky

- Organizational learning

- Organization workshop

- Social constructivism (learning theory)

- Vygotsky Circumvolve

- Zone of proximal development

Publications [edit]

- Akkerman, Sanne F.; Bakker, Arthur (2011). "Boundary Crossing and Boundary Objects". Review of Educational Research. 81 (2): 132–169. doi:10.3102/0034654311404435. S2CID 53685507.

- Andersson, Gavin (2004). Unbounded Governance: A Study of Popular Development Organization. UK: Open Academy.

- Andersson, Gavin; Richards, Howard (2012). "Bounded and Unbounded Arrangement". Africanus. 42 (1): 98–119. ISSN 0304-615X

- Andersson, Gavin (2013). The Activity Theory Arroyo (PDF). Seriti, S.A.: (pre-booklaunch) chapter from Unbounded Organization:Embracing Societal Enterprise. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 November 2013. Retrieved 26 January 2015.

- Bakhurst, David (2009). "Reflections on Action Theory". Educational Review. 61 (2): 197–210. doi:10.1080/00131910902846916. S2CID 145198993.

- Bedny, K.; Karwowski, W. (2006). A Systemic-Structural Theory of Activity: Applications to Human Operation and Work Pattern. Boca Raton, CRC Press/Taylor & Francis. ISBN978-0849397646.

- Bedny, G.Z.; Karwowski, W.; Bedny, I. (2014). Applying Systemic-Structural Activity Theory to Design of Human-Estimator Interaction Systems. CRC Printing. ISBN9781482258042.

- Blunden, Andy (2009). Soviet Cultural Psychology. Archived from the original on viii July 2015. Retrieved 26 January 2015.

- Blunden, Andy (2011). An Interdisciplinary Theory of Activity. Haymarket Books. ISBN9781608461455.

- Bozalek, Vivienne; et al. (2014). Activity Theory, Authentic Learning and Emerging Technologies: Towards a transformative college educational activity teaching. Routledge. ISBN978-1138778597.

- Carmen, Raff; Sobrado, Miguel (2000). A Future for the Excluded. London, United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland: Zed Books. CiteSeerX10.1.1.695.1688. ISBN9781856497022.

- Castells, Manuel (2001). The Net Milky way: Reflections on the Cyberspace, Business, and Lodge. Oxford University Press, Inc. New York, NY, The states 2001. ISBN978-0199241538.

- Cole, Michael (1996). Cultural Psychology. A One time and Futurity Subject area. Nebraska Symposium on Motivation. Nebraska Symposium on Motivation. Vol. 37. Harvard University Press Harvard MA. pp. 279–335. ISBN978-0-674-17951-6. PMID 2485856.

- Cole, Michael; Engeström, Yrjö; Vasquez, Olga (1997). Mind, Culture and Activity. Cambridge University Press. USA. ISBN978-0-521-55238-vii.

- CRADLE, (Centre for Enquiry on Activeness, Development and Learning) (2009). Cultural-Historical Activity Theory. Finland: University of Helsinki. Archived from the original on 26 January 2015. Retrieved 26 January 2015. .

- Daniels, Harry; Warmington, Paul (2007). "Analysing third generation activity systems: labour power, field of study position and personal transformation". Periodical of Workplace Learning. 19 (6): 377–391. doi:ten.1108/13665620710777110.

- Daniels, Harry; Edwards, Anne; Engeström, Yrjö; Gallagher, Tony; Ludvigsen, Sten (2010). Action Theory in Practise. Promoting learning across boundaries and agencies. Routledge London. ISBN978-0-415-47725-3. OCLC 244057445.

- Edwards, Anne (2011). Cultural Historical Activity Theory (Conversation) (PDF). Oxford. UK: BERA (British Educational Research Association).

- Engeström, Yrjö (1987). Learning past Expanding: An Activity-theoretical arroyo to developmental enquiry (PDF). Helsinki, Finland: Orienta-Konsultit.

- Engeström, Yrjö (1993). Developmental studies of work as a testbench of activity theory: The case of primary care medical practise. In: South. Chaiklin & J. Lave (Eds.), Understanding practice: Perspectives on activity and context. (pp. 64–103) . Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Engeström, Yrjö; Virkkunen, Jaakko; et al. (1996). The Change Laboratory equally a tool for transforming work (PDF). Eye for Activity Theory and Developmental Work Research. University of Helsinki.

- Engeström, Yrjö; Miettinen, Reijo; Punamäki, Raija-Leena (1999). Perspectives on Activeness Theory. Cambridge Academy Printing. ISBN9780521437301.

- Engeström, Yrjö (1999c). Learning by expanding: x years later (Translation from the High german by Falk Seeger). online.

- Engeström, Yrjö (1999a). Engeström's (1999) outline of iii generations of activity theory (PDF). Univ Bath webpage.

- Engeström, Yrjö (1999). "Expansive Visibilization of Work: An Activity-Theoretical Perspective". Computer Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW). 8 (1–2): 63–93. doi:ten.1023/A:1008648532192. S2CID 8480841.

- Engeström, Yrjö (2001). "Expansive Learning at Work: toward an action theoretical reconceptualization" (PDF). Periodical of Educational activity and Work. Journal of Education and Piece of work, Vol 14, No i. 14: 133–156. doi:ten.1080/13639080020028747. S2CID 56227598.

- Engeström, Yrjö (2004). New forms of learning and co-configuration work (PDF). online LSE London presentation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 July 2007. Retrieved 26 January 2015.

- Engeström, Yrjö (2005a). Developmental Work Enquiry: Expanding Activity Theory in Practice. Lehmanns Media, Berlin. International cultural-historical human sciences Series Bd 12. ISBN9783865410696.

- Engeström, Yrjö (2005). "Knotworking to Create Collaborative Intentionality Majuscule in Fluid Organizational Fields". Knotworking to create collaborative capital in fluid organizational fields. Advances in Interdisciplinary Studies of Work Teams. Vol. 11. Elsevier Advances in Interdisciplinary Studies of Work Teams Volume 11, 307–336. pp. 307–336. doi:10.1016/S1572-0977(05)11011-5. ISBN978-0-7623-1222-ane. ISSN 1572-0977.

- Engeström, Yrjö (2007). Putting Vygotsky to work: the Change Laboratory as an awarding of double stimulation in: Due south. Daniels, Chiliad. Cole & J.V.Wertsch (Eds.), The Cambridge Companion to Vygotsky. (pp. 363–382) . Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Engeström, Yrjö; Keresuo, Hannele (2007). "From workplace learning to inter-organizational learning and back: the contribution of activeness theory". Journal of Workplace Learning. 19 (6): 336–342. doi:ten.1108/13665620710777084.

- Engeström, Yrjö (2009a). Expansive learning: Toward an activity-theoretical reconceptualization. Educação & Tecnologia 2, 2009.

- Engeström, Yrjö (2009b). Wildfire Activities: New Patterns of Mobility and Learning (PDF). International Journal of Mobile and Blended Learning, Volume ane, Issue 2.

- Engeström, Yrjö; Sannino, Analisa (2009). "Studies of expansive learning: Foundations, findings and futurity challenges" (PDF). Educational Research Review. 5: 1–24. doi:10.1016/j.edurev.2009.12.002.

- Human foot, Kirsten (2014). Cultural-Historical Action Theory: Exploring a Theory to Inform Practice and Research (PDF). University of Washington. U.s.a..

- Hardman, Joanne (2007). Making sense of the significant maker: tracking the Object of activity in a computer-based mathematics lesson using action theory. International Journal of Instruction and Development, 3:four(110—130).

- Hasan, Helen (2007). A Cultural-Historical Activeness Theory Approach to Users, Usability and Usefulness (PDF). Australia: Academy of Wollongong.

- Igira, Faraja, T.; Gregory, Judith (2009). Cultural Historical Activeness Theory (PDF). IGI Global. – Chapter 25 in: Yogesh K. Dwivedi, Y.K. Lal, B., Williams, M., Schneberger, Southward.Fifty., Wade, M., 2009, Handbook of Research on Contemporary Theoretical Models in Data Systems, IGI Global, 2009, ISBN 9781605666594

- Jonassen, David; Land, Suzan (2012). Theoretical Foundations of Learning environments. Routledge second edition. ISBN9780415894210.

- Kaptelinin, Victor; Nardi, Bonnie A. Activeness theory: bones concepts and applications. online ACM New York, NY, United states of america 1997.

- Kaptelinin, Victor (2005). "The Object of Action:Making Sense of the Sense-Maker". Mind, Culture, and Activity. 12: 4–eighteen. doi:10.1207/s15327884mca1201_2. S2CID 9466871.

- Kaptelinin, Victor; Nardi, Bonnie A. (2006). Acting with Technology: Action Theory and Interaction Design. MIT Printing. ISBN978-0262513319.

- Labra, Iván (1992). Psicología Social: Responsabilidad y Necesidad – Social Psychology. Responsibleness and Demand (in Castilian). LOM Ediciones, Republic of chile. ISBN978-9567369522.

- Labra, Isabel; Labra, Ivan (2012). The Organization Workshop Method. Laboratories on the Objectivized Activity (PDF). Seriti, S.A.: Integra Terra Network Editor. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 November 2013. Retrieved 26 January 2015.

- Labra, Iván (2014). A Critique of the Social Psychology of Small Groups & an Introduction to a Social Psychology of the Large Group (PDF). IntegraTerra – Chile: (pre-booklaunch) Intro & Chapter I. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 April 2014. Retrieved 26 January 2015.

- Lave, Jean; Wenger, Etienne (1991). Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge University Press. ISBN978-0-521-42374-eight.

- Leontiev, Aleksei Nikolaevich (1977). Activity and Consciousness (PDF). P.O. Box 1541; Pacifica, CA 94044; United states of america.: Marxist Net Annal (2009). ISBN978-0-9805428-3-seven.

{{cite volume}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Leontiev, Aleksei Northward (1978). Activity, Consciousness, and Personality. Prentice-Hall – Translated by Marie J. Hall. OCLC 3770804.

- Leontiev, A.N. (1979). The trouble of Activity in Psychology (PDF). Armonk, NY. Sharpe. in: Wertsch 1981, p. 37–78

- Leontiev, Aleksei Nikolaevich (1981). The Development of Mind – Selected Works of A.Due north. Leontyev – Foreword K.Cole (PDF). P.O. Box 1541; Pacifica, CA 94044; Usa.: Marxist Cyberspace Archive (2009). ISBN978-0-9805428-iii-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Leontiev, A.N. (1984). Actividad, Conciencia y Personalidad (Spanish). Cartago Ediciones, México.

- Leontiev, Alexei, Nicolayevich (2009). The Evolution of Mind. Erythrós Press, Kettering, OH.

- Luria, A.R. (1976). The Cerebral Development: Its Cultural and Social Foundations. Harvard Academy Press. ISBN978-0-674-13731-8.

- Miettinen, Riejo (2005). "Object of Activity and Private Motivation". Mind, Culture, and Activity. 12: 52–69. doi:10.1207/s15327884mca1201_5. S2CID 145476624.

- Morais, Clodomir, Santos de (1979). Apuntes de teoría de la organización – Notes on theory of Organization (in Spanish). Managua, Nicaragua: PNUD, OIT-NIC/79/010, COPERA Project.

- Nardi, B.A., ed. (1996). Context and Consciousness: Action Theory and Human-Computer Interaction . MIT Printing, Cambridge, MA.Us. ISBN978-0262140584.

Nardi, B.A. (ed.), Context and Consciousness: Activity Theory and Homo-.

- Nussbaumer, Doris (2012). "An Overview of cultural historical action theory (CHAT) apply in classroom enquiry 2000 to 2009". Educational Review. 64: 37–55. doi:ten.1080/00131911.2011.553947. S2CID 143592550.

- Nygård, Kathrine (2010). Introduction to Cultural Historical Activity Theory (CHAT) (PDF). INTERMEDIA Univ. of Oslo.

- Roth, Wolff-Michael (2004). "Action Theory and Didactics: An Introduction". Mind, Culture, and Activity. eleven: 1–8. doi:x.1207/s15327884mca1101_1. S2CID 144857387.

- Roth, Wolff-Michael; Lee, Yew-Lin (2007). ""Vygotsky's Neglected Legacy": Cultural-Historical Activity Theory". Review of Educational Research. 77 (2): 186–232. CiteSeerXx.one.one.584.7175. doi:10.3102/0034654306298273. S2CID 12099538.

- Roth, Wolff Michael; Radford, Luis; Lacroix, Lionel (2012). "Working With Cultural-Historical Activeness Theory". Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research. 13 (2).

- Sannino, Annalisa; Daniels, Harry; Gutiérrez, Kris D. (2009). Learning and Expanding with Activity Theory (PDF). Cambridge University Press. ISBN9780521758109.

- Soegaard, Mads & Dam; Friis, Rikke, eds. (2013). The Encyclopedia of Human-Computer Interaction, 2nd Ed. The Interaction Blueprint Foundation, Aarhus, Kingdom of denmark.

- Spinuzzi, Dirt (2011). Losing past Expanding:Coralling the Delinquent Object. Journal of Business organisation and Technical Communication, October 2011; vol. 25, 4: pp. 449–486.

- Spinuzzi, Dirt (2012). "Working Lone Together: Coworking as Emergent Collaborative Activity". Journal of Business and Technical Communication. 26 (4): 399–441. CiteSeerX10.1.1.679.2427. doi:x.1177/1050651912444070. S2CID 110796881.

- Spinuzzi, Clay (2014). "How Nonemployer Firms Phase-Manage Ad Hoc Collaboration: An Activeness Theory Assay". Computer Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW). 8 (ii): 63–93. doi:x.1080/10572252.2013.797334. hdl:2152/28329. S2CID 143660330.

- Spinuzzi, Clay (2018). "From Superhumans to Supermediators: Locating the boggling in Conversation". In Yasnitsky, Anton (ed.). Questioning Vygotsky's Legacy: Scientific Psychology or Heroic Cult. New York & London: Routledge. pp. 131–160. doi:x.4324/9781351060639. ISBN9781351060639.

- Stetsenko, Anna (2005). Confronting Belittling Dilemmas for Understanding Complex Human being Interactions in Design-Based Research From a Cultural–Historical Activity Theory (Chat) Framework (PDF). Mind, Civilisation & Action, 12/1. pp. 70–88.

- UNESCO, ibedata (1979). Terminology of Adult Education (trilingual en-es-fr) . Paris, Fr.: UNESCO. ISBN978-9230016838.

- van der Riet, Mary (2010). Using Activity Theory to Understand Human Behaviour – Office II. University of KwaZulu Natal. South Africa.

- Virkkunen, Jaakko (2006). Dilemmas in building shared transformative agency (PDF). Middle for Activeness Theory and Developmental Work Research Helsinki/ Activités revue électronique.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 26 January 2015.

- Vygotsky, Lev Due south. (1978). Mind in Lodge: the Evolution of Higher Psychological Processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Academy Press. ISBN978-0-67457629-2.

- Wertsch, James (1981). The Concept of Activeness in Soviet Psychology. M.E.Sharpe. ISBN9780873321587.

- Yamagata-Lynch, Lisa C. (2007). "Confronting Analytical Dilemmas for Understanding Complex Human being Interactions in Blueprint-Based Research from a Cultural-Historical Activity Theory (CHAT) Framework". Periodical of the Learning Sciences. 16 (4): 451–484. doi:x.1080/10508400701524777. S2CID 58183848.

- Yamagata-Lynch, Lisa C. (2010). Activeness Systems Analysis Methods. Agreement Circuitous Learning Environments. Springer. ISBN978-one-4419-6320-viii.

- Yamazumi, K (17 August 2009). Expansive Agency in Multi-Activity Collaboration. in:Sannino, Daniels & Gutiérrez 2009, p. 212. ISBN9780521760751.

Notes and references [edit]

- ^ Or activity theory (AT), as it is also known. Kaptelinin & Nardi 2006, p. 36

- ^ Nardi 1996, p. vii notes that activity theory is a "a research framework and set of perspectives", not a hard and fast methodology or strongly predictive single theory.

- ^ a b Daniels et al. 2010

- ^ a b c Kaptelinin & Nardi 2006

- ^ Roth & Lee 2007, p. 192: "CHAT was conceived of as a concrete psychology immersed in everyday praxis": "consciousness is located in everyday practice: you are what y'all do" Nardi 1996, p. 7

- ^ In the 1920s till the mid 1930s.

- ^ Yasnitsky, A. (2018). Vygotsky: An Intellectual Biography. London and New York: Routledge BOOK PREVIEW

- ^ Leontiev may at times too be spelled as Leontyev and Leont'ev.

- ^ a b Engeström, Miettinen & Punamäki 1999

- ^ It is well known that the Soviet philosopher of psychology S.L.Rubinshtein, independently of Vygotsky's work, developed his own variant of activity equally a philosophical and psychological theory. re: V. Lektorsky in Engeström, Miettinen & Punamäki 1999, p. 66;Brushlinskii, A. Five. 2004 Archived i September 2014 at archive.today. Engeström would be happy to also include [in the account of A.T.] reference to Luria, Zinchenko (father, Peter, and son, Vladimir), Elkonin, Davydov and Brushlinsky (as well as to various other figures who have influenced activity-theory in the W, such as Dewey, Mead, and Wittgenstein). Bakhurst 2009, p. 201

- ^ Political restrictions in its country of origin (Stalinist Russian federation) had suppressed the cultural-historical psychology – also known every bit the Vygotsky School – in the mid-thirties. This meant that the core "activity" concept remained confined to the field of psychology, although Blunden 2011, in "An Interdisciplinary Theory of Activity", argues that information technology has the potential to evolve equally a genuinely interdisciplinary concept. See besides Nussbaumer 2012, p. 37

- ^ a b c d Vygotsky 1978

- ^ Kaptelinin & Nardi 2006 Introduction

- ^ CHAT explicitly incorporates the mediation of activities past lodge, which means that it tin can exist used to link concerns normally independently examined past sociologists of didactics and (social) psychologists. Roth & Lee 2007 and Roth, Radford & Lacroix 2012

- ^ a b Leontiev 1978

- ^ Activity Theory in a Nutshell. Ch three in Kaptelinin & Nardi 2006.

- ^ Cole 1996, p. 105

- ^ The activity theoretical framework, as recently equally the 1990s, was still referred to as "one of the best kept secrets of academia" Engeström 1993, p. 64; Roth & Lee 2007, p. 188

- ^ Prominent amongst those currents are Cultural-historical psychology, in use since the 1930s, and Activity theory in use since the 1960s.

- ^ a b Stetsenko 2005

- ^ a b c Yamagata-Lynch 2007

- ^ In detail Goethe's romantic science Archived iii October 2015 at the Wayback Machine ideas which were later on taken up by Hegel. The pregnant of "activity" in the conceptual sense is rooted in the German word Tätigkeit. Hegel is considered the kickoff philosopher to point out that the development of humans' knowledge is non spiritually given, simply developed in history from living and working in natural environments.

- ^ Blunden, A. 2012, "The Origins of Cultural Historical Activity Theory" Archived 27 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine ; Blunden, A. Genealogy of Chat (graph).

- ^ Blunden 2011, p. 18

- ^ Vygotsky 1978, p. 40

- ^ "A man individual never reacts directly (or merely with inborn reflexes) to the surroundings. Consciousness and witting action must be the central object of written report for psychological science, since it is this that distinguishes humanity. The relationship between human agent and objects of the surround is mediated by cultural ways, tools and signs. Human action has a tripartite structure."(CRADLE 2009)

- ^ At the beginning of and into the mid-20th century, Psychology was dominated by schools of thought that ignored real-life processes in psychological performance (due east.grand. Gestalt psychology, Behaviorism and Cognitivism (psychology)).

- ^ For a history of what came to be known as the Kharkov School of Psychology re: Yasnitsky & Ferrari, 2008 in: History of Psychology Vol. xi, No. 2, 101–121.

- ^ Veer and Valsiner, 1991

- ^ When Stalin succeeded Lenin in 1924, the Soviet Matrimony gradually turned into a dictatorship. This led to thirty years of stagnation during which intellectuals and academics who deviated from the Stalinist credo were politically attacked for their work and eventually eliminated. Vygotsky's colleagues had to flee to Ukraine for prophylactic. Sannino & Sutter, 2011 p. 563. Stalin died in 1953 and restrictions were subsequently gradually relaxed.

- ^ Fraser, J.; Yasnitsky, A. (2015). "Deconstructing Vygotsky'due south Victimization Narrative: A Re-Examination of the "Stalinist Suppression" of Vygotskian Theory" (PDF). History of the Homo Sciences. 28: 128–153. doi:10.1177/0952695114560200. S2CID 4934828.

- ^ Wertsch 1981

- ^ In the tardily 1970s, an unabridged generation of Soviet psychologists died: Luria and Meshcheryakov died in 1977, Leontiev and Ilienkov in 1979. (Ilienkov by his own hand. – see: Blunden, 2009 "Soviet Cultural Psychology" Archived 8 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine).

- ^ due east.1000.: Luria's "The Making of Mind" translated by Cole.

- ^ Blunden, 2009 Archived 8 July 2015 at the Wayback Car.

- ^ The earliest books translated into English are Lev Vygotsky'southward "Idea and Language"(1962), Luria's "Cerebral Evolution" (1976), Leontiev's Action, Consciousness, and Personality (1978) and Wertsch'south "The Concept of Activity in Soviet Psychology" (1981).

- ^ "Historians may come to place in Michael Cole the unmarried most influential person for acquainting Western scholars to this tradition, both through his writings and through the mediating role of his Laboratory for Comparative Human Noesis (LCHC) at the Academy of California, San Diego" (Roth & Lee 2007, p. 190).

- ^ Other notable CHAT specialists: Jaan Valsiner (Estonian – Clark Academy), René van der Veer (Dutch – Leiden Academy) and Dorothy (Dot) Robbins Archived 10 Apr 2015 at the Wayback Machine (German– University of Central Missouri)

- ^ Other Chat-based centers of inquiry and learning: Oxford Center for Sociocultural and Activeness Theory Inquiry Archived 5 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine (OSAT), International Society o Cultural and Activeness Research(ISCAR), LCSD: Laboratory of Comparative Human Cognition (LCHC), Kansai University (Japan) CHAT: Center for Activity Theory Archived 28 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine. BERA British Educational Research Clan [ permanent dead link ] (Conversation Special Interest Grouping).

- ^ History of ISCRAT Archived 12 Jan 2005 at the Wayback Machine(International Standing Conference for Enquiry, on Activity Theory)

- ^ Carl Shames, 1989 "On a significant coming together in West Berlin"

- ^ at present known equally CRADLE, subsequently the merger with the Centre for Research on Networked Learning and Knowledge Building at Helsinki

- ^ (Selective) listing of other Chat-related research groups and centers: ATUL Archived fourteen Feb 2017 at the Wayback Auto (Activeness Theory Usability Laboratory at the University of Wollongong Commonwealth of australia – "Organisations and communities of the Cognition Historic period"). ; Conversation Archived 28 July 2017 at the Wayback Motorcar (Center for Human Action Theory, Kansai Academy, Japan – "Links with Helsinki, Bathroom and California"). ; OSAT Archived 5 Feb 2015 at the Wayback Auto (Oxford Centre for Sociocultural and Activity Theory Research at Oxford University Great britain. – "Learning across the historic period range".) ; LIW (Learning in and for Interagency Working at the University of Bathroom, UK – "Effective multiagency working".)

- ^ For other scholars/practitioners involved with CHAT see: "People in Cultural-Historical Activity Theory".

- ^ a b c d e f thousand Engeström 1987

- ^ 'Generations' does not imply a 'amend-worse' value judgment. Each illustrates a different attribute and exists in its own right.

- ^ a b Engeström 2009b

- ^ a b c Yamagata-Lynch 2010

- ^ Nussbaumer 2012

- ^ a b Engeström 1999a

- ^ Bakhurst 2009, p. 199

- ^ An activity arrangement is a collective in which 1 or more homo actors labor to cyclically transform an object (a raw material or trouble) in social club to repeatedly achieve an event (a desired result). Spinuzzi 2012, p. 5

- ^ Yamagata-Lynch, Lisa C.; Haudenschild, Michael T. (2009). "Using activeness systems analysis to place inner contradictions in teacher professional development". Instruction and Teacher Educational activity. 25 (3): 507–517. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2008.09.014. ; Engeström, 2008, "The Future of Activity Theory" p. half-dozen.

- ^ a b c Akkerman & Bakker 2011

- ^ Vygotsky saw the past and present as fused within the individual, that the "present is seen in the light of history" (Vygotsky 1978).

- ^ These artifacts, which tin be physical tools, such as hammers, ovens, or computers; cultural artifacts, including language; or theoretical artifacts, similar algebra or feminist standpoint theory, are created and/or transformed in the course of an activity, which, in the first generation framework, happens at the individual level.

- ^ Wells, M (2007). "Semiotic Mediation, Dialogue and Structure of Knowledge" (PDF). Human Development. 50 (5): 244–274. CiteSeerXten.1.1.506.7763. doi:10.1159/000106414. S2CID 15984672.

- ^ Vygotsky 1978, p. 40: this original diagram – (in which "X" stands for 'mediation') – has subsequently been reformulated by, among others, the original triangle being inverted.

- ^ Engeström 2001, p. 134. Vygotsky'due south triangular representation of mediated activity attempts to explain human consciousness evolution in a manner that did not rely on dualistic stimulus–response (Southward-R) associations.

- ^ "the dialectic relationship between bailiwick and object as a primal unit of analysis for all human endeavour" Hasan 2007, p. 3.

- ^ For Vygotsky's thought of a "complex, mediated human activity" ordinarily expressed as a triad of subject, object and mediating artifact, see Vygotsky 1978, p. 40.

- ^ Vygotsky makes the point that "homo himself determines his behavior with the assistance of an artificially created stimulus means." (every bit cited past Norris Minick in Vol I of "The Collected Works of L.S. Vygotsky", 1987, PLENUM – New York/London, p.21);

- ^ Mediation is perhaps the key theoretical idea behind activity: we don't simply use tools and symbol systems; instead, our everyday lived experience is significantly mediated and intermediated by our use of tools and symbols systems. Activity theory helps frame, therefore, our understanding of such mediation.

- ^ In Vygotskyan psychology internalization is a theoretical concept that explains how individuals process what they learned through mediated action in the development of individual consciousness.

- ^ Vygotsky 1978, p. 86 – Restated, ZPD is the theoretical range of what a performer can practise with competent peers and assistance, as compared with what can exist accomplished on 1'south own(Andersson 2013, p. 21; DeVane & Squire in Jonassen & Land 2012, p. 245).

- ^ see for example Collaborative learning.

- ^ Leontiev, (variously spelled Leont'ev/Leontyev) was, with Alexander Luria, one of Vygotsky's pupils in the late 1920s and 1930s. After Vygotsky'southward death, Leontyev became the main theoretical correspondent within the Vygotskian social-historical schoolhouse.

- ^ Leontiev's quantum was twofold: commencement he theorized activeness as resulting from the confluence of a homo bailiwick, the object of his/her activity (predmet/Предмет(Russian) "the target or content of a idea or action" (Kaptelinin, 2005, p. vi), and the tools (including symbol systems) that mediate the object(ive); 2d, he saw activity equally essentially tripartite in structure, being composed of unconscious operations on/with tools, witting only finite actions which are goal-directed, and college level activities which are object-oriented and driven by motives (Leontiev, at times, seems to conflate object and motive, which is potentially problematic).

- ^ Engeström 1987 first popularized the triangular representation of the activity system in chapter two.

- ^ While the unit of measurement of assay, for Vygotsky, is "individual activeness" and, for Leontiev, the "collective action system", for Jean Lave and others working around situated cognition the unit of measurement of analysis is "exercise", "community of practice", and "participation". Other scholars clarify "the relationships betwixt the private's psychological development and the evolution of social systems". re: Minick in Cole, Engeström & Vasquez 1997, p. 125; Lave & Wenger 1991

- ^ Leontiev 1979, p. 163;Engeström 1999, p. 30

- ^ Hardman 2007

- ^ In the second generation diagram, activity is positioned in the middle, mediation at the top, adding rules, community and partitioning of labor at the lesser. The minimum components of an activity arrangement are: the subject; the object; upshot; mediating instruments/tools/artifacts; rules and signs; community and division of labor.

- ^ Leontiev 1981, p. 210–213

- ^ Kuutti, K. in Nardi 1996, p. thirty; Roth & Lee 2007; Hardman 2007; Bozalek 2014, p. xv.

- ^ Leontiev 2009, p. 400–405 ; Blunden 2011, p. 201; Nussbaumer 2012, p. 39; DeVane & Squire in Jonassen & Land 2012, p. 247

- ^ Engeström in Engeström, Miettinen & Punamäki 1999, p. 19

- ^ "[Activity Theory] is non only used in Russia, where it originated, merely besides in Australia, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Frg, Italia, Japan, Norway, Due south Africa, Sweden, Switzerland, the Great britain, the United States and other countries.". (Kaptelinin & Nardi 2006, p. 6)

- ^ "Activities do not exist in isolation, they are part of a broader system of relations in which they have meaning." (Lave & Wenger 1991, p. 53.)

- ^ a b c d Engeström 2001

- ^ a b Engeström 2009a

- ^ Roth & Lee 2007, p. 210

- ^ Run into "Activity Systems Assay" (ASA) section beneath.

- ^ Blunden 2011, p. 3

- ^ Engeström 2001, p. 137.

- ^ Nygård 2010

- ^ Jonassen & Land 2012, p. 242

- ^ Hardman 2007 Introduction: "A flurry of recent publications indicates that Activity Theory is proving a useful tool for studying piece of work setting" She mentions, among others, Product design, Collaborative action, Studies in creativity, Educational interventions. Although not as widely known in the Usa, Kirsten Foot mentions use of Conversation in Educational curricula development, Mental health intendance, Organizational processes and Public policy.

- ^ More than recently, Engeström has best-selling that the third-generation model limited to analysing 'reasonably well-bounded' systems and that, in view of new, often web-based participatory practices a rethink is needed. (See "Fourth Generation" below.)

- ^ Erik Axel

- ^ From the original Предметная деятельность(Russian) (predmetnaja-dejatelnost) and Gegenständliche Tätigkeit(German), commonly translated as "Actividad Objetivada"(Spanish) – encounter: Leontiev 1984, p. 66, and as Objective Activity in English: e.g. Chapter 3 of Leontiev 1978, p. 50ss, Wertsch 1981, p. 46ss and Miettinen 2005 Abstract:'Leontiev's concept of practise or Objective Action'. (For "Objectivis/zed", see e.chiliad.: Leontiev 1978, p. 116: "Activeness's secondary objectivised existence" and Leontiev 1977, p. 404: "the mental image objectivised in its product"). "Objectivized Action" is perceived to be closer to both the alphabetic character and the spirit of dynamic, interactive, dialectical weighting of Leontiev'south original predmetnaya dyaetel'nost.

- ^ "Laboratories on Objectivized Activity" in: Labra & Labra 2012; Labra 1992: "Actividad Objetivada"(Spanish) p. 53; "de Morais' antecedent thought on Objectivised Activity" in Andersson 2004, p. 221 ss; Carmen & Sobrado 2000, p. 118 & note No. 2.

- ^ Andersson 2013, p. 5ss (Pre booklaunch chapter from "Unbounded Arrangement: Embracing the Societal Enterprise").

- ^ Many of whom, historically, unemployed or underemployed persons with 'Lower Levels of Literacy' (LLLs)

- ^ Andersson 2013, p. 31

- ^ Mutizwa Mukute, M.& Lotz-Sisitka, H. 2012 "Working With Cultural-Historical Activity Theory and Critical Realism to Investigate and Expand Farmer Learning in Southern Africa". Rhodes University. SA.

- ^ a b Foot 2014

- ^ In 1997, according to Santally et al., 2014, p. 3

- ^ Sannino, 2008 "From Talk to Action: Experiencing Interlocution in Developmental Interventions" Sannino sees in Yves Clot'due south Vygotsky-inspired Clinic of Activeness (Clinique de 50'Activité) a potentially complementary – (to CL, that is) – intervention method. (See also Jell, Yves, 2009 Dispensary of Activity: The Dialogue every bit Instrument in Sannino, Daniels & Gutiérrez 2009).

- ^ Which became CRADLE in 2008.

- ^ a b Engeström 2005a

- ^ Expansive learning is described by Engeström 2009a, p. 130 equally a procedure which "begins with individual subjects questioning accepted practices, and information technology gradually expands into a collective motion or institution. – The theory enables a "longitudinal and rich analysis of inter-organizational learning [] past using observational as well as interventionist designs in studies of work and system". (Engeström & Kerosuo, 2007)

- ^ a b Engeström & Virkkunen 1996

- ^ CRADLE 2009

- ^ Virkkunen, Makinen & Lintula in Daniels et al. 2010, p. 15

- ^ Engeström & Sannino 2009

- ^ Engeström. Y. in: Engeström, Miettinen & Punamäki 1999, p. 384

- ^ Contradictions are not merely conflicts or problems, but are "historically accumulating structural tensions within and between activeness systems" (Engeström 2001, p. 137).

- ^ e.g. Mukute, Chiliad., 2009 Archived 28 Jan 2015 at the Wayback Motorcar

- ^ Teräs, M., 2007

- ^ Kerosuo, H., 2006

- ^ Engeström, 2011

- ^ Santally et al., 2014

- ^ Other examples, among others, in Daniels et al. 2010

- ^ Which uses Activity Theory concepts such as mediated action, goal-directed activity and dialectical relationship between the organism and the environment.

- ^ Cole, Chiliad., & Engeström, Y. (1993). "A cultural–historical arroyo to distributed cognition" in: Salomon, 1000 (Ed), 1993.

- ^ Yamagata "Activity Systems Analysis Methods

- ^ Engeström 1993

- ^ Jonassen, David H.; Rohrer-Irish potato, Lucia (1999). "Action theory as a framework for designing constructivist learning environments". Educational Technology Inquiry and Development. 47 (1): 61–79. doi:ten.1007/BF02299477. S2CID 62209169.

- ^ Yamagata-Lynch, Lisa C. (2003). "Using Activeness Theory as an Analytic Lens for Examining Technology Professional Development in Schools". Listen, Civilisation, and Activeness. 10 (2): 100–119. doi:x.1207/S1532-7884MCA1002_2. S2CID 143340720.

- ^ Yamagata-Lynch, Lisa C.; Smaldino, Sharon (2007). "Using activity theory to evaluate and ameliorate Chiliad-12 school and university partnerships". Evaluation and Program Planning. 30 (4): 364–380. doi:ten.1016/j.evalprogplan.2007.08.003. PMID 17881055. – For ASA and (computer-based) mathematics didactics see e.one thousand. Hardman 2007

- ^ Human-Figurer Interaction – the study, planning, blueprint and uses of the interfaces betwixt people (users) and computers.

- ^ Kuutti in Nardi 1996, p. 17

- ^ Kaptelinin & Nardi 2006, p. 15

- ^ Kaptelinin, Victor "Activity Theory" in Soegaard & Friis 2013

- ^ Bødker, S. "A Homo Activity arroyo to User Interfaces" in: Human-Estimator Interaction, 1989, Volume 4, pp.171–195

- ^ Nardi 1996

- ^ Bedny, G.; Karwowski, W. (2003). "A Systemic-Structural Activity Approach to the Design of Human–Computer Interaction Tasks". International Journal of Man-Computer Interaction. 16 (2): 235–260. CiteSeerXx.ane.i.151.8384. doi:ten.1207/s15327590ijhc1602_06. S2CID 16212346.

- ^ Bedny, Karwowski & Bedny 2014; Bedny, I. S.; Karwowski, West.; Bedny, Chiliad. Z. (2010). "A Method of Homo Reliability Assessment Based on Systemic-Structural Activity Theory". International Periodical of Human-Calculator Interaction. 26 (4): 377–402. doi:10.1080/10447310903575507. S2CID 32705523. ; Bedny & Karwowski 2006;

- ^ Crossing boundaries involves "encountering difference, inbound into [] unfamiliar territory, requiring cognitive retooling". Tuomi-Grōhn & Engeström, 2003, "New Perspectives on Transfer and Boundary Crossing" p.4.

- ^ Engeström 1999c

- ^ Kuutti, N. Ch 2 in Nardi 1996

- ^ Miettinen in Engeström, Miettinen & Punamäki 1999, p. 325 "Transcending traditional school learning: Teachers' work and networks of learning."

- ^ Wikipedia, launched in 2001, is one of the most successful instances of networked learning to engagement.

- ^ Engeström & Keresuo 2007

- ^ a b Sannino, Daniels & Gutiérrez 2009

- ^ a b Engeström 2004

- ^ Spinuzzi 2011; Spinuzzi 2012

- ^ meet e.g. Castells 2001

- ^ a b Spinuzzi 2014

- ^ Software, the source code of which is available for modification or enhancement by anyone.

- ^ Social production processes are simultaneous, multi-directional and often reciprocal. The density and complexity of these processes blur distinctions between process and structure. The object of the activity is unstable, resists control and standardization, and requires rapid integration of expertise from various locations and traditions. (Engeström in Sannino, Daniels & Gutiérrez 2009, p. 309)

- ^ run into eastward.g. Engeström in: Hughes, Jewson & Unwin, 2007 Ch. 4.

- ^ see e.chiliad. Spinuzzi, 2010: shift from bureaucracies (1970s), to adhocracies (1990s), to all-border adhocracies (2010s), in: "All Border: Understanding the New Workplace Networks".

- ^ Past 2008, Engeström's examples go 'less bounded': runaway objects – or 'partially shared large-scale objects in complex, distributed multi-activity fields'-, wildfire, and mycorrhizae-like activities, are examples of this shift. (Engeström 2009b; Engeström in Sannino, Daniels & Gutiérrez 2009, p. 310; Spinuzzi 2011).

- ^ aka "4GAT" east.chiliad. Spinuzzi 2014

- ^ Sannino, Daniels & Gutiérrez 2009, p. 310 Ch. 19 "The Future of Activity Theory: A rough draft."

- ^ Fourth-Generation (4GAT) analysis should allow improve test of how activity networks interact and interpenetrate, and, at times, contradict each other. People "working alone together" may illuminate other examples of distributed, interorganizational, collaborative knowledge work.Spinuzzi 2014

- ^ Yamazumi 2009

- ^ For an example of a quaternary generation analytical diagram see Spinuzzi 2014, p. 104

External links [edit]

- Blunden, A. The Origins of CHAT.

- Blunden, A. Concepts of CHAT Action, Behaviour and Consciousness (ppts).

- Blunden, A. Genealogy of Cultural Historical Activity Theory (nautical chart)

- Boardman, D. Activeness Theory

- CRADLE Helsinki

- Interview with Professor Yrjö Engeström: function 1

- Interview with Professor Yrjö Engeström: role 2

- Introduction to Cultural Historical Activeness Theory (CHAT) Nygård

- Leontiev works in English

- Robertson, I. An Introduction to Action Theory

- Spinuzzi, Clay "All Border: Understanding the New Workplace Networks" (Powerpoint Presentation)

- The Hereafter of Action Theory

- van der Riet Part I Introduction to Cultural Historical Activity Theory (Conversation)

- van der Riet Part 2 Using Activity to Understand Man Behaviour

- Vygotsky archive

- Yamagata "Activeness Systems Analysis in Design Research". (Powerpoint Presentation)

- What is Action Theory?

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cultural-historical_activity_theory

Belum ada Komentar untuk "Everyday Life and Cultural Theory an Introduction Review"

Posting Komentar